Read in the Kindle edition

Book 1 - Inside Mr Enderby, published under the pseudonym Joseph Kell in 1963. We first meet Enderby through the eyes of a group of time travelling school children, on an educational trip to visit some of the poets of yesteryear. There are echoes of Joyce Grenfell in the teachers admonitions to the students not to misbehave, which of course they do. Enderby lives alone, in squalor. His bathroom is his sanctum, where he composes his poetry, filing much of it in the bath which he shares with a family, indeed generations, of mice. He lives a narrow, routine existence, troubled by the outside world as little as possible. But people just won't leave him alone.

Nasty neighbours and a nosy landlady are a nuisance, but his problems really start when he wins a literary prize, which he accepts in person at an event in London - or rather doesn't accept, his speech getting away from him somewhat. After that he loses control of his life. Vesta Bainbridge, women's editor of "Fem", takes him in hand, and begins the arduous task of transforming him into husband material. She succeeds to the extent of getting him in a fit state for their marriage but the change is temporary, and he manages to escape from her (on their honeymoon in catholic Rome) as she rapidly transforms herself into his dead step-mother. At some point, apparently angered by his betrayal, his muse, always conceived as a literal companion, deserts him. Seeing no future without poetry, Enderby attempts suicide. He attempt fails, and we leave him in a rest home undergoing a cure to rid him of his infantile obsession with poetry and its trappings.

Book 2, Outside Enderby. The psychiatric transformation of our hero is no more effective nor long lasting than Vesta's attempt, and with the return of his muse, Enderby is about to leave his job as a barman when fate once more intervenes. The bar where he works is being used as a venue for a pop group - the lead singer of which has plagiarised some of his poetry, left behind in his flight from Vesta's home. The singer is shot by a bitter former band member, but Enderby is framed, and flees. Taking a holiday flight to Tangiers, narrowly escaping the clutches of a matronly astrologer on the way, he tracks down Rawcliffe, a failed former poet who had plagiarised his extended poem, the Pet Beast, turning it into a schlock horror film script. Rawcliffe, who is in all the anthologies, is dying, and Enderby cares for him in his last days, instead of killing him as intended. Enderby inherits Rawcliffe's bar, and settles down into a comfortable life of exile. But the happy ending is denied him, because at the end of the novel he is visited - literally - by a personification of his muse, who is a cruel mistress, and who appears to intend to desert him, once again.

It appears that Burgess planned books one and two as a single volume, and only published them separately when a serious illness threatened to be (indeed was diagnosed as) terminal. But having created this character it seems Burgess couldn't really leave him alone.

Book 3, A Clockwork Testament, or the End of Enderby, finds Enderby lecturing in creative writing and minor Elizabethan drama in New York. He is more of a fish out of water than ever, finding much in New York and his students to frustrate and anger him. This is a lighter revival of Enderby, putting him in comic situations in which his frustrations with the modern world are never far from the surface. Enderby makes no compromises for his new situations, and is blunt to the point of being offensive towards his black students, particularly in his liberal use of the N-word - what would have read as challenging and daring in the 1970s comes across as simply offensive in 2012, not that Burgess would have given a stuff. But this is true of many treatments of this issue, and we should be wary about imposing 21st century values on 1970s Britain, or any other period for that matter. Which I suppose is his point.

The discussion about the potentially corrupting influence of art, as exemplified by the popular response to the vulgarised film treatment of "The Wreck of the Deutschland" dominates much of the novel. This is Burgess's response to the media storm generated by the film of Clockwork Orange, hence the otherwise inexplicable title of the third novel in the series, in case the point were to be missed (which of course it is now much easier to do, with Kubrick's film available to watch on terrestrial television, and pretty tame stuff compared to, for example, the Saw movies.)

The fourth and last Enderby novel, Enderby's Dark Lady, or No End to Enderby, in which Burgess imagines what might have happened to our hero if he had not taken the post in New York. Here he is offered a role scripting a musical representation of the life of Shakespeare, variously entitled Will! Or An Ass for an Actor (check!!) in a very different part of America, rural Indiana. Here is as much a fish out of water as anywhere else, and comes in for a lot of stick from the cast, crew, financial backers, and the community generally. He becomes besotted with the female lead, April Elgar, a gorgeous African American, who befriends him and who allows Burgess plenty of opportunities to demonstrate his scholarship and knowledge about Shakespeare's dark lady of the sonnets.

The fourth and last Enderby novel, Enderby's Dark Lady, or No End to Enderby, in which Burgess imagines what might have happened to our hero if he had not taken the post in New York. Here he is offered a role scripting a musical representation of the life of Shakespeare, variously entitled Will! Or An Ass for an Actor (check!!) in a very different part of America, rural Indiana. Here is as much a fish out of water as anywhere else, and comes in for a lot of stick from the cast, crew, financial backers, and the community generally. He becomes besotted with the female lead, April Elgar, a gorgeous African American, who befriends him and who allows Burgess plenty of opportunities to demonstrate his scholarship and knowledge about Shakespeare's dark lady of the sonnets.

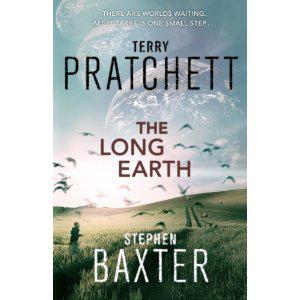

The musical is of course chaotic, and on the opening night Enderby has to take the part of Will, which he does triumphantly (after his own fashion) - ad-libbing, breaking the fourth wall, ignoring an intervention from a US Equity equivalent representative who tries to stop the show, ending in a dance of the beginning of the world on stage with April. Instead of the usual time travelling tourists, Burgess book-ends the story with more erudition about Will and Elizabethan theatre - a story about spying and the theatre in Shakespeare's time to open, including a theory on Shakespeare's involvement in the development of the St James' edition of the bible which I have never taken the time to follow up but if taken at face value appears very convincing, and ending with a science fiction tale about a time traveller going to an alternative 1590's London to meet Shakespeare. The trip doesn't end well, but this stand alone story is a far more interesting treatment of the parallel worlds theory than "The Long Earth".

Why is Enderby such an endearing, successful character? He meets many of the criteria you would look for in a sit-com character - good hearted but hopelessly adrift in the modern world, always falling unwittingly into comic situations, and at the same time puzzlingly attractive to various maternal and not so maternal women. For Enderby poetry is the all-consuming mistress that he cannot allow himself to be distracted from. The comedy switches from quite low brow, scatological stuff to highbrow meditations on Elizabethan theatre and Shakespearean scholarship.

Burgess's style, throughout the quartet, is one of the major enjoyments of the novels. He plays with language freely, at times showing off, but rarely distracting from the overall fun of the piece. Here's an example from Book 2. Enderby is serving drinks in a bar when he meets an old acquaintance, whose breath, he notices, smells of onions:

"Then, instead of expensive mouthwash, he had breathed on Hogg-Enderby, bafflingly (for no banquet would serve, because of the known redolence of onions, onions) onions. "Onions" said Hogg."

I can just imagine Burgess's pleasure at meeting the no doubt self imposed challenge of repeating "onions" four times consecutively without interruption nor syntactic trickery.

I've read these novels for pleasure several times since discovering Inside Enderby many years ago, and apart from the easily offended they should be a joy for all readers. I cannot recommend them highly enough.