Bendrix survives, in fact is largely unhurt, and true to her perverse bargain with god, Sarah leaves him. Leaves is a misleading term, in that she has never actually left her husband, who working late at the Ministry and already living a sexless life, doesn't notice the affair. She finds the separation painful, so perversely pursues other affairs - the deal with god was very specific apparently - but eventually relents and decides to resume the relationship. The reader is invited to see the hand of god in the various bits of fairly clumsy sit-com style incidents that prevent this resolution being carried out, and Sarah finally succumbs to the irresistible charms of the Catholic Church, before catching a cold and dying. Colds are pretty ferociously dangerous in romantic novels; in fact it would be nice some time soon to read a novel where the resolution is not provided by someone conveniently dying, even if the death as here is signposted a long way in advance, and comes as nothing of a surprise. Cuckolder and cuckolded commiserate one another after Sarah's death, and eventually become an odd couple of their own, pottering down to the pub each night to drown their sorrows.

Bendrix survives, in fact is largely unhurt, and true to her perverse bargain with god, Sarah leaves him. Leaves is a misleading term, in that she has never actually left her husband, who working late at the Ministry and already living a sexless life, doesn't notice the affair. She finds the separation painful, so perversely pursues other affairs - the deal with god was very specific apparently - but eventually relents and decides to resume the relationship. The reader is invited to see the hand of god in the various bits of fairly clumsy sit-com style incidents that prevent this resolution being carried out, and Sarah finally succumbs to the irresistible charms of the Catholic Church, before catching a cold and dying. Colds are pretty ferociously dangerous in romantic novels; in fact it would be nice some time soon to read a novel where the resolution is not provided by someone conveniently dying, even if the death as here is signposted a long way in advance, and comes as nothing of a surprise. Cuckolder and cuckolded commiserate one another after Sarah's death, and eventually become an odd couple of their own, pottering down to the pub each night to drown their sorrows. Much of the novel is dominated by a discussion of religion, and more specifically Catholicism. God intervenes in the life of the characters, and while they resist fiercely, they eventually accept his gifts. Even though Bendrix ends the novel by rejecting the roman god, he does so more through stubbornness and anger than any lack of belief. Frankly, this is largely tedious, unconvincing preaching - of course god can appear in the lives of characters if the author simply invents "coincidences" to persuade them of his existence. Rosencrantz and Guildernstern in Stoppard's play about their deaths show infinitely more faith in the power of coincidence, denying the existence of an external power, even when that power is the author himself. All it takes here, by comparison, are some simple coincidences before Bendrix begins to start doubting his agnosticism, ending with a suggestion reminiscent of the conversion at the end of "Brideshead" that he too has accepted the inevitable (even if this suggestion comes at the very beginning of the novel: "If I had believed then in a God".)

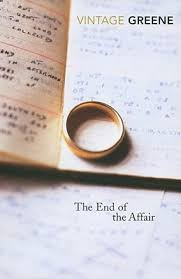

In an insightful introduction in this Vintage edition, Monica Ali surgically pinpoints many of the faults in the novel - the poor characterisation in particular, and the failure of the religious conversion scenes. I agree, but I think she is too kind on Greene. We are invited to see Bendrix as a tragic anti-hero - he is the victim of his own sad story - but if you remove his point of view from the events of the novel and look a little more objectively, he is really a nasty piece of work. He cuckolds Miles, simply at first to get some material for his novel. He has sex with Sarah in her own house while Miles is upstairs, and later has sex with her in a ditch, overlooked by a farmer on a tractor who passes "at the moment of crisis". Nothing gets in the way of his determination to sleep with Sarah - at one point he even is grateful for the war for the opportunities it provides: "War had helped us in a good many ways" (page 45). He is casually arrogant about his writing and his attractiveness to women, and treats his lover appallingly, employing a private detective, the gormless hat-tipping Parkis, to steal her diary.

Greene's reputation as one of England's foremost post-war novelists cannot be evaluated on the strength of a single novel, but this is not a strong exhibit for the defence. 'The End of the Affair' is a confidence, well constructed novel full of strong descriptions and turns of phrase, but I suspect it won't linger long in the memory. It has not aged well - I appreciate that 1951 was a long time ago, but there is a bit of a dated, Edwardian feel to this tale - the characters still have maids to answer the door. Perhaps I need to take a look at 'Brighton Rock' or 'Our Man in Havana' after a suitable period of reflection?

No comments:

Post a Comment